At around 3 a.m. on the Jan. 4, 2024, hundreds of armed officers took control of People’s Park on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, CA. The Park was closed off by the University as part of its $312 million plan to build on-campus student housing. The once public park has now been sealed shut by blue and yellow shipping containers along its perimeters - with private security guards manning the area at all times.

The case was brought against the Regents of the University of California in 2021 to halt construction on the People’s Park - which would add 1,100 beds for students and 100 for the unhoused. “The University has plans to build on every available site where there isn't a current use,” said Dan Mogulof, Assistant Vice-Chancellor an the University's Office of Communications and Public Affairs.

Berkeley has a housing problem. The problem started decades ago - when the University ramped up enrollment without considering what that would mean for the city, its residents and students who were swarming inside the city to attend college. The problem finally culminated with a judge ordering UC Berkeley to freeze enrollments at 2020 levels.

However, housing insecurity among students still persists. The overcrowding of students and under-availability of housing has led to an imbalance where today, only 22% of all enrolled students live in on-campus housing according to the latest numbers provided by the University.

“The city of Berkeley is not in any position to provide services for all the Cal students who are experiencing homelessness. Homelessness services in Berkeley just can't absorb all the students,” said Coco Auerswald, a professor at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health.

According to University data, each incoming batch is larger than 10,000 students keeping the student population hovering close to 50,000 students at any given time. But the rate at which students are being enrolled isn’t proportional to the rate at which housing is being added - creating very little change in the living situation of students.

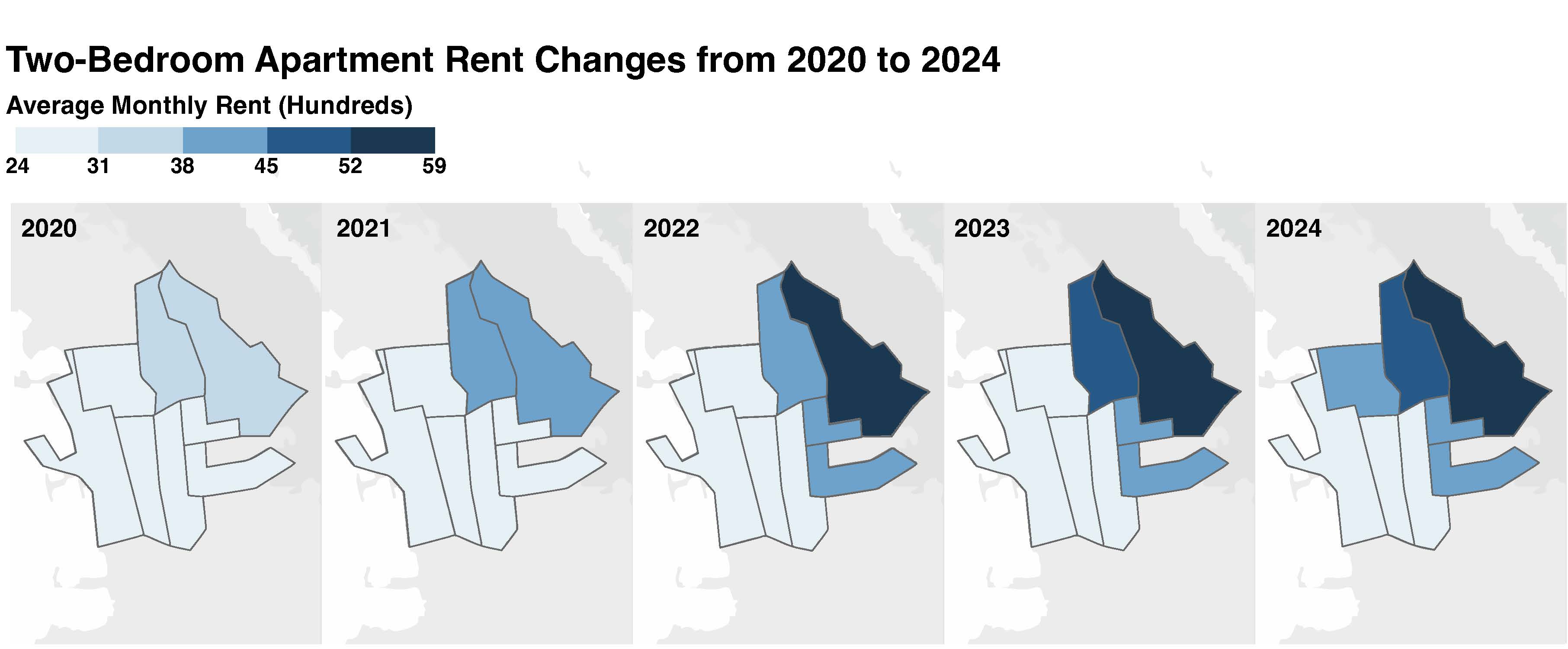

Not only does this make finding enough housing difficult, it also creates an imbalance in the demand and supply of places to live - for everyone in the city. Rent prices have shot up in the city as a result of an exploding population of students - add that to the already expensive housing in the Bay Area and now rent in some neighborhoods in Berkeley pushes comfortably over $4,000.

According to UC Berkeley’s new housing plan that was brought forth by Chancellor Christ when she was elected in 2017 was to add 9,000 beds for students. But how much of a difference will that make to a student population of several thousand in one city?

According to results of the Student Pulse Survey for Spring 2024, out of the 5,695 students that responded, 31% pay between $1,000 - $1,500 per month and 22% pay above $2,000. The housing plans have proposed 9,000 beds for students - the goal is still to be able to provide 2-year permanent housing to incoming freshmen, 1-year to transfer students and 1-year to incoming graduate students. However, nothing has been said about the proposed rents and fees for these housing units.

What does that mean for students who can’t afford to live in a city with rents touching $4,000?

Enrique (Rico) Marisol moved to Berkeley as a freshman at UC Berkeley in 2019. In 2020, once the pandemic hit and the University allowed students to end their leases prematurely, Marisol ended their lease and moved in with their parents for the summer. Soon after, they came back to Berkeley and found themself without housing.

They couch-surfed for a couple of months before moving into an apartment where they shared a bathroom with five other people during the peak of the pandemic. “All of my belongings that I had was in two suitcases at one point. That’s all I had,” says the 23-year-old.

What it means to be unhoused or homeless is difficult to define according to Marisol. Many students don’t like to describe themselves as homeless on surveys out of embarrassment. Many students who couch-surf or live in their cars don’t consider themselves homeless at all.

“You know, when you're open to it as a faculty member, students come out of the woodwork and there are so many students who are experiencing homelessness. If people don't identify as such, they may not get the services they need,” said Auerswald.

The primary federal law that established protections to children and youth living in homelessness, The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act defines homeless children and youth as those “who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence,” including those who share spaces in others houses, live in trailer parks, motels or camping grounds and those who live in public spaces including cars or bus stations.

Being unhoused or housing insecure could pose significant health risks that may impact the future well-being of young people. “People are exposed to poor nutrition, they're exposed to poor sleep and they don't really have time for self-care because they're focused on basic needs,” said Auerswald. "They're also suffering from social isolation a lot of the time because if you don't have a place to stay - your identity is highly stigmatized in our society," she added.

According to Auerswald, many students are currently unhoused and in need of help that the University and city aren’t equipped to provide. And while organizations including the Basic Needs Center exist within the University to address these issues, the extent of the problem is simply too large and urgent.

Beginning in 2021, the Park has been prepped in various phases for the eventual construction of a housing unit which is presumed to house over 1,000 students. After testing soil samples within the Park in 2021, the University ordered the cutting of some of the historic Redwoods in the area in the following year - both years, it was met with protestors.

Originally home to indigenous people, the land was bought by the University of California, Berkeley in 1967. In April 1969, the residents of Berkeley came together to create what we now know as the People’s Park. Only the next month, the California Highway Patrol on the orders of the then-President Ronald Regan occupied the city and subsequently, the Park. In the protests that followed to protect the space, one person was killed and 128 were injured - it came to be known as ‘Bloody Thursday.’

On May 20, 1969, Regan sent the National Guard to restore order which resulted in thousands of residents marching across the city in dissent. A year later, the park was liberated. Ever since, the People’s Park has been home to many unhoused in the community.

However, over the years, the Park had developed a reputation of being an area with high drug use cases. “And the other reason that we spent millions of dollars in offered people sleeping in the park transitional housing, is because since people started sleeping in the park with the start of the pandemic, it's become a locus of crime, where by and large, the people targeted by the criminals, the victims of the crime, are the unhoused people sleeping in the park,” said Mogulof.

The California Supreme Court, while hearing arguments on April 3rd appears to be moving in the direction that would give the University a green light to begin construction on the People’s Park site.